The Mirabel Rape Allegation: Viral Outrage, Glaring Loopholes, and What We Actually Know

For roughly three days in mid-February, Nigeria’s vast and restless digital public fixated on a single name. Mirabel. It first appeared in whispers on TikTok, then in all-caps outrage on X, and finally in somber Instagram stories framed by candle emojis and clenched fists.

By the time Lagos State officials acknowledged they were searching for her, millions of Nigerians already felt they knew her story, had grieved with her, and had decided who was to blame.

Trending Now!!:

It was a story told in fragments, but with extraordinary force. A young woman, her face close to the camera, her voice cracking as if under physical strain, said she had been raped in her Lagos apartment by a man who forced his way in while she was intoxicated and asleep.

Afterward, she said, he contacted her online and sent her a message that read less like remorse than like a manifesto of cruelty.

In it, he described the assault, mocked her economic vulnerability, and boasted that his father’s money would ensure the case never reached court. He ended with a line so chilling it seemed designed to linger in the reader’s mind: I love you, don’t see me as a bad person, okay.

Within hours, hashtags demanding justice for Mirabel were trending. Influencers vowed to help track down the attacker. Ordinary users flooded her comments with messages of love and promises that she was not alone. Nigeria, a country where sexual violence is widespread and convictions are rare, seemed briefly united in fury and sympathy.

But as the story raced ahead of verification, as reposts multiplied faster than facts, a quieter question hovered beneath the noise. What did we actually know?

The first video began circulating widely on Monday, February 16, 2026, though Mirabel said the events she described had occurred the previous day. In the clip, she explained that she suffered from chronic insomnia.

To cope, she said, she often drank alcohol or used other substances to sleep. On the night of Saturday, February 14, bleeding into the early hours of Sunday, February 15, she drank heavily and did not fall asleep until around 6 a.m.

At about 9 a.m., she said, she was jolted awake by a knock on her door. Still intoxicated and groggy, she assumed it was a neighbor, perhaps someone returning from church. She opened the door. “Immediately I opened the door, I got pushed back,” she said in the video. “Before I got to my door, there was my fridge, and a few steps forward, there was my door. I hit my head on the fridge. I passed out.”

When she regained consciousness, she said a man was on top of her. A cloth had been stuffed into her mouth and tied to keep her quiet.

She tried to make noise, hoping a neighbor might hear, but believed most people in the building were away at church. She estimated the assault lasted more than 20 minutes. When it was over, the man left. She later noticed blood. At first, she thought it was her period.

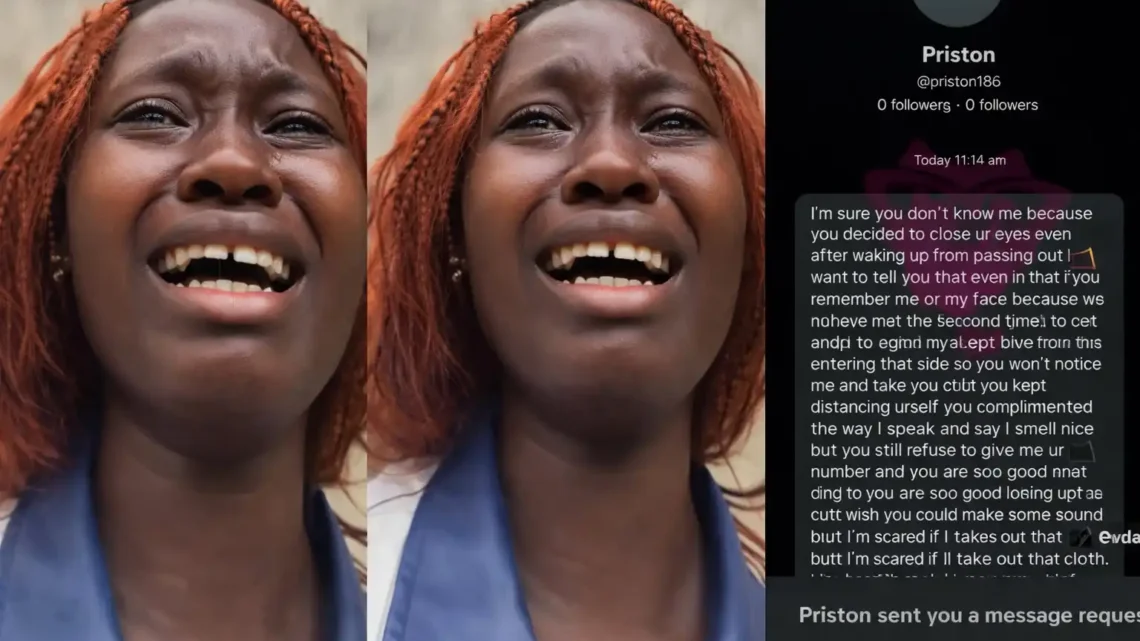

On its own, the account was harrowing but not unprecedented. What turned it into a national obsession was what followed. Mirabel posted screenshots of a message she said she received afterward on TikTok, from an account with the handle priston186.

The message, written in casual vernacular, claimed responsibility for the rape. It began by asserting familiarity. “We have met twice,” the sender wrote, adding that she had ignored him the second time. He said she had complimented his speaking voice and remarked that he smelled nice, but refused to give him her phone number.

He claimed he had spent money to locate her apartment. He then described the assault in graphic terms, including cutting her with what he called a face blade, a razor commonly used for grooming. He said he did this “to simulate me being the first person there.” He mocked her reaction and her circumstances.

“My father has the money to bury the case right before it gets to court,” he wrote. “So don’t bother my darling. You can’t find me, and you don’t even have the money to, considering your situation, you are feeding from hand to mouth.”

Then came the line that seemed to crystallize public rage. “I will come back for you in 4–5 years’ time and date you,” he wrote. “I love you, don’t see me as a bad person, okay.”

The message ricocheted across the internet. Screenshots were reposted thousands of times, often without Mirabel’s name blurred, sometimes accompanied by calls for vigilante justice. The alleged attacker was quickly cast as a symbol of everything Nigerians despise about sexual violence: entitlement, misogyny, and the belief that wealth confers immunity.

By Monday afternoon, the hashtags #JusticeForMirabel and #StopRapingWomen were trending. By evening, major Nigerian blogs had published summaries of the story.

By Tuesday morning, established news organizations had joined in. Premium Times reported that the Lagos State Domestic and Sexual Violence Agency was trying to locate Mirabel. Vanguard and The Guardian followed with similar reports.

The Lagos DSVA issued a statement acknowledging the reports. “We want to state clearly that we have seen the reports,” the agency said, “and we are actively making efforts to reach the survivor to offer immediate support and appropriate intervention, and ascertain the location.” The statement emphasized that the agency had not yet made contact. “Our team has initiated contact through available channels and will continue efforts to establish communication,” it said.

The agency appealed to the public for help. “If anyone has credible information that can assist us in reaching her directly and safely, please contact the Agency by sending us a DM on any of our official social media channels,” it said. It listed phone numbers, a toll-free line, and a USSD code.

The Lagos State Police Command echoed the call. Its public relations officer, SP Abimbola Adebisi, wrote on X that the command was aware of the case and had forwarded it to the gender unit. “I have also reached out to her through her TikTok handle,” she wrote. “I sincerely hope she responds to assist the Police in conducting a thorough investigation.”

For many observers, the official response felt unusually swift. In a country where survivors often struggle to get police to take reports seriously, the existence of a gender unit and a specialized agency issuing public statements within days suggested progress. But it also underscored a limitation. Authorities could not investigate a crime or support a survivor they could not find.

On Tuesday afternoon, Mirabel posted a second video. This one was shorter, her voice softer. She said she had attempted suicide the previous day by drinking Sniper, a highly toxic pesticide widely known in Nigeria for its lethality.

“I took a sniper yesterday,” she said, “and my friend came back and saw me in the backyard and took me to the hospital.” She thanked people who had tried to reach out to her and apologized for not responding. “My phone is in DND,” she said. “I can’t text. I’m so sorry.”

The revelation sent another shock through social media. Sympathy deepened. Urgency intensified. If the assault had not already been enough, the suicide attempt seemed to confirm the depth of her distress.

Prominent influencers amplified the story further. VeryDarkMan, a controversial but influential activist with a large following, posted a video reading portions of the alleged message and vowing to ensure justice. Others followed suit. The Lagos Police Command confirmed again that the case was with the gender unit.

The speed of the story’s spread became a story in itself. Within 72 hours, a TikTok video had mobilized activists, drawn official responses, and sparked nationwide debate. Yet for all the noise, the factual foundation remained thin. Almost every detail in circulation traced back to Mirabel’s own videos and the screenshots she shared.

This is where discomfort sets in, and where careful scrutiny becomes essential. To question elements of a rape allegation is not to deny the prevalence or horror of sexual violence. Trauma often produces fragmented narratives.

Survivors may minimize prior contact with an assailant, misremember timelines, or struggle to articulate details. But investigative rigor exists precisely to separate what is emotionally compelling from what is verifiable.

One of the most significant gaps concerns prior acquaintance. Mirabel described the attacker as a stranger who forced his way into her home. The alleged message, however, insisted they had met twice before. If that claim is true, the man was not a random intruder but someone who knew her at least superficially. That distinction does not reduce the severity of the crime, but it does affect how it is understood and investigated.

If they had met twice, how did he know where she lived? He claimed he spent money to locate her apartment.

In Lagos, where informal networks can uncover personal information for a fee, this is not implausible. But it raises further questions. Would someone who went to such lengths truly know nothing else about her? Or does the public version of their relationship omit details she chose not to share?

Another critical point concerns the alleged use of a razor blade. Sexual assaults involving sharp objects typically result in injuries that require medical attention and are evident upon examination. Mirabel said she noticed bleeding but initially thought it was her period.

It remains unclear whether she sought medical care immediately after the assault or only after her suicide attempt. If she is hospitalized, as she said, there should be medical records documenting her condition. Whether a forensic examination was conducted, and when, could be decisive.

The suicide attempt itself adds a tragic but potentially corroborating layer. Drinking Sniper is extremely dangerous. Survival usually involves emergency treatment and leaves clear toxicological evidence. Hospital admission records could confirm her account of timing and severity.

They could also provide authorities with a way to locate and support her. As of the time of writing, no hospital had publicly confirmed treating her, and officials had not said they had made contact.

There is also the matter of the digital evidence. The TikTok account priston186 was described by some users as having neither followers nor following. That could indicate a burner account created specifically to send the message.

It could also mean the account was deleted or altered after the screenshots were taken. Only TikTok, responding to a formal law enforcement request, can determine whether the account is linked to a real person, where it was accessed from, and whether it can be traced to a device or IP address.

Perhaps the most perplexing aspect of the case is the disconnect between Mirabel’s visibility online and her apparent inaccessibility to authorities. She was able to post two videos to millions of viewers. She was repeatedly tagged in posts from the DSVA and the police.

Yet she had not, at least publicly, contacted them directly. There are compassionate explanations for this. Trauma can render people incapable of navigating bureaucracy. Fear, distrust of police, and sheer overwhelm can all play a role. Setting a phone to do not disturb during a viral moment is understandable. But without her cooperation, the path to justice narrows.

The broader context makes these questions even more fraught. Sexual violence in Nigeria is both pervasive and under-prosecuted. Survivors face stigma, victim-blaming, and pressure to remain silent.

Conviction rates are low, even in states with specialized courts. Many cases collapse for lack of evidence or are quietly settled out of court. It is precisely this reality that drives survivors to seek validation and protection online.

In some instances—like the 2019 case of a young woman gang-raped in a hotel in Edo State, social media pressure forced a police investigation that led to arrests. In others, allegations have crumbled under scrutiny.

The case of “Fem Thrift,” another TikTok user who reported being raped after a modeling shoot just days before Mirabel‘s story broke, has been taken seriously by the Ikeja Gender Unit, showing that the system can work.

So, the proliferation of unverified claims also creates a dangerous dynamic. Fabricated or exaggerated stories, however rare, are weaponized by those who wish to discredit all survivors. Every loophole in Mirabel’s account will be used by rape apologists to argue that “women lie.” This is why rigorous, empathetic investigation is not the enemy of justice—it is its guardian.

At the same time, viral justice carries its own dangers. The same crowd that offers support can turn hostile if inconsistencies emerge. Fabricated or exaggerated claims, though rare, are seized upon by those eager to discredit all survivors. Every loophole in Mirabel’s account risks being weaponized to reinforce the myth that women lie about rape.

Nigeria has seen this cycle before. Some viral cases have led to arrests and convictions, propelled by sustained public pressure. Others have unraveled, leaving bitterness and mistrust in their wake. Each instance shapes how future allegations are received.

As of February 18, 2026, there is no concrete evidence that the Mirabel case is a hoax. Her emotional distress appears genuine and not at the same time. The alleged message contains a level of specificity and vernacular that suggests it was written by a real person.

It is entirely plausible that a man, rejected after prior encounters, stalked and assaulted her. But significant elements remain unverified. The exact nature of their relationship, the existence and timing of medical examinations, the traceability of the digital account, and even her current location are unknown to the public.

What happens next matters not only to Mirabel but also to the integrity of justice in the age of virality. Authorities must make private, direct contact with her and move her out of the digital spotlight into a protected support system.

A forensic investigation, if still possible, must be conducted with care. Digital records must be preserved and analyzed through formal channels. The public must resist the urge to demand constant updates or additional performances of trauma.

The Mirabel case has already revealed much about Nigeria’s collective conscience. It has shown a deep well of empathy and a growing intolerance for sexual violence. It has also shown how quickly outrage can outpace evidence. Holding both truths at once is uncomfortable but necessary.

For now, Mirabel deserves privacy, protection, and medical care. If the man who claimed responsibility exists and is who he says he is, he deserves to learn that in 2026, money and bravado are not guarantees of impunity. The truth lies somewhere beyond the screenshots and the hashtags. Finding it is the work of investigators, not the internet.