Alade Street Will Never Forget That July

It was one of those humid Lagos evenings in July when the air feels thick enough to chew.

Power had been out since morning, so everybody was outside—kids playing ten-ten, aunties fanning themselves with old newspapers, guys clustered around a phone watching a match. Our compound on Alade Street had that familiar low buzz of people trying not to suffocate in their own houses.

Trending Now!!:

Emeka was already tipsy by 7 p.m. He’d started with the small stout someone brought back from the viewing centre, then moved to the palm wine his cousin smuggled in a jerrycan. By the time the sky turned that bruised purple, he was loud-laughing at everything, slapping backs too hard, doing that thing where he pretends to be a boxer, shadow-punching the air.

Nobody took it seriously when he said, “I fit fly this roof go down straight.” We’d heard worse boasts from him. Last December, he swore he could jump the gutter behind the mechanic shop and land on both feet—he didn’t, twisted his ankle for two weeks, and still limped dramatically whenever he wanted sympathy.

But that night, the roof was calling him.

Our block had that flat concrete roof everybody used for drying clothes, storing old buckets, and occasionally sleeping when the rooms turned into ovens. There was a rusty iron ladder bolted to the side of the building—more holes than rungs in places. Emeka climbed it like he was proving something to the whole compound.

“Watch me now,” he shouted down. “I go show una say person fit be superhero for this life.”

His girlfriend, Ifeoma, was already tired. “Emeka, come down abeg, this one no be film.” She stood at the base of the ladder with arms folded, wrapper tied high like she was ready to drag him if necessary.

He reached the top, spread his arms wide as he’d seen in too many action movies, then started walking the narrow ledge that ran along the edge. Maybe five feet wide, parapet only coming up to shin height. People started gathering properly now—phones out, some laughing, some already hissing “this boy don high finish.”

He got to the corner where the building faced the narrow alley, turned back to face us, and did a little bow. That was when the joking stopped feeling funny.

“Emeka!” someone shouted—maybe me, maybe Chinedu. “Come down before you wound yourself.”

He laughed that big, careless laugh. Then he said the sentence that still plays in my head sometimes when it’s too quiet: “If I die today, at least una go remember say I try.”

He took two running steps.

Not a graceful leap. Not a calculated jump. Just drunk momentum and bad judgment.

He cleared the edge.

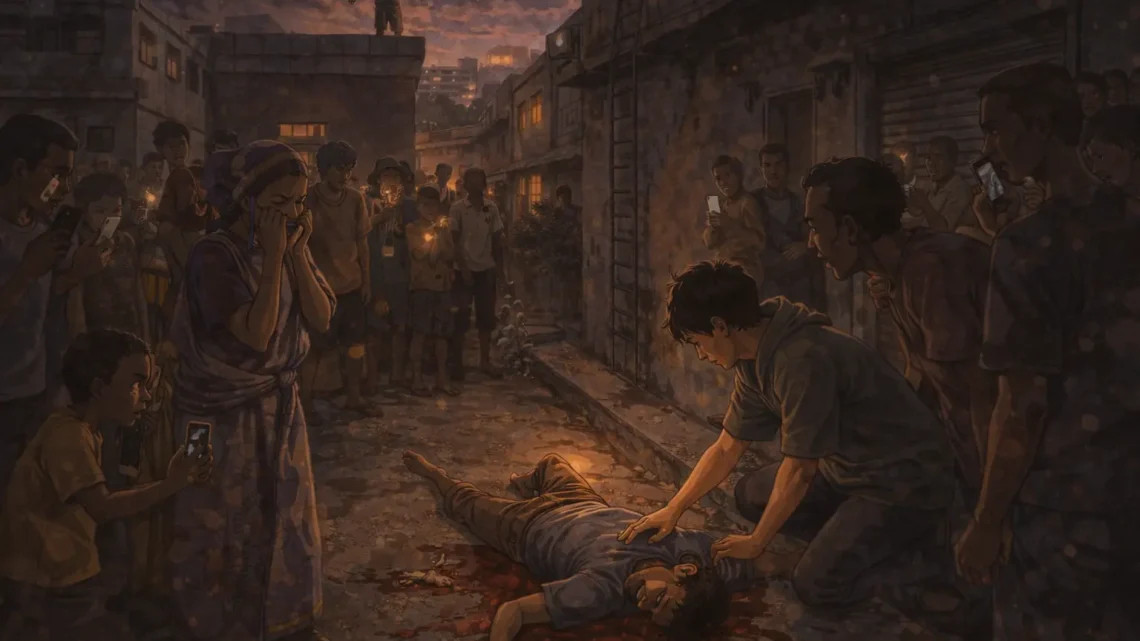

For maybe one full second, everybody froze—mouths open, phones still recording. Then the sound hit: wet meat against concrete, followed by the sickening crack of something important breaking.

He landed in the alley between our block and the abandoned plumber’s shop next door. Face-down. One leg bent completely the wrong way. Blood was already spreading under his head like spilled palm oil.

Ifeoma screamed first—a raw, animal sound. Then chaos. People running, shouting for water, shouting for an Okada, shouting for God. Someone called his name over and over like repetition would undo physics.

I got to him before most people. Turned him gently. His eyes were open but not focused. Breathing shallow, wet rattles. Blood coming from his ear, his nose, his mouth. The side of his skull looked… wrong.

He tried to speak once. Just bubbles of blood and a soft “sorry.” Then nothing.

The ambulance took forever—almost forty minutes. By the time they got him to Lagos Island General, the doctor only shook his head after five minutes of checking. Massive head trauma, shattered femur, internal bleeding they couldn’t stop even if the theatre was ready. He was already gone.

The compound was quiet for weeks after that. Nobody used the roof except to collect clothes before the rain. The ladder got padlocked. People avoided looking up there, like the concrete itself had become guilty.

Sometimes at night, when the gen is off, and it’s too hot to sleep, I still hear his laugh echoing off that roof. Not the drunk one. The real one he used to have before life started pressing him too hard.

He was twenty-six.

Just wanted to feel like he could fly for three stupid seconds.

Nobody’s climbed that roof since. Not even the kids. They say it’s cursed now.

Maybe it is.